When Tom Waits warned on "Underground," the first song on his transformational 1983 album Swordfishtrombones, "there’s a rumblin’ groan down below," he very well could have been describing the artistic awakening that made him a legend.

Once an earnest yet good-humored singer/songwriter, Tom Waits is the rare artist in the past 50 years to successfully pull off something as radical as a complete artistic reinvention. A songwriter with a taste for the dark and grotesque as much as the theatrical, Waits has built up a catalog heavy on bizarre characters, morbid nursery rhymes, gruff junkyard blues and a uniquely unconventional take on rock music. And though it took some experimentation, trial and error and eventually getting married to arrive on the sound we hear today, he’s made a five-decade career of embracing sounds on the fringe and turning them into memorable melodies.

A Southern California native who got his start playing folk clubs in San Diego before relocating to Los Angeles in the 1970s, Tom Waits debuted as a relatively conventional singer/songwriter with a twinge of blues and jazz in his bones. And where his earliest records found him singing with more of a raspy croon, he adopted a vocal growl more spiritually akin to Louis Armstrong and Captain Beefheart.

Waits never quite fit in alongside peers such as Jackson Browne or James Taylor. His instincts often pushed himself somewhere a little dirtier and darker, favoring tales of vagabonds and outcasts told with an inebriated sentimentality and irreverent humor. Throughout his decades-long career, the two-time GRAMMY winner never let go of the emotional honesty in his songwriting.

Waits has joked that he makes two types of songs: grim reapers and grand weepers. The former became his staple sound in the 1980s after he married longtime creative partner Kathleen Brennan and began his decade-long tenure on Island Records, which still occasionally found him returning to the latter via less frequent but no less disarming ballads.

What once was a songbook reflective of the bars and familiar streets evolved into surreal dens of iniquity and theaters of the grotesque. Waits' knack for storytelling and character development only strengthened over the years, even as his songs took more oddball and ominous shape. Swordfishtrombones' "Sixteen Shells from a Thirty-Ought Six" follows a hunter following a crow into a Moby Dick-like epic; spoken word standout "What’s He Building In There?," from 1999’s Mule Variations, prompts the listener to ponder who’s really up to no good.

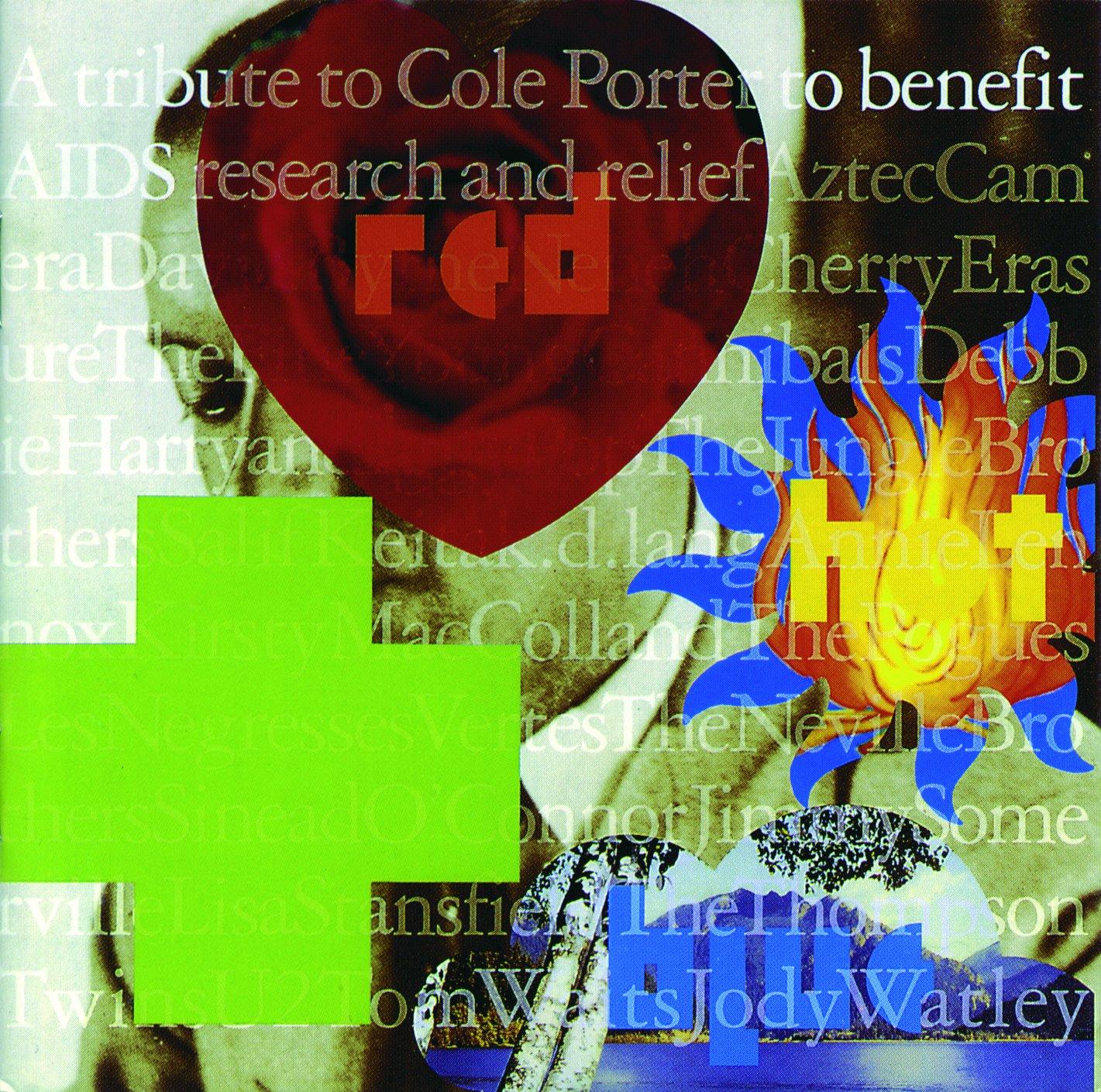

Though his record sales have been modest, Waits' songs have been covered by the likes of Rod Stewart and Eagles, and he’s collaborated with everyone from Bette Midler to Keith Richards. His songwriting and unique musical aesthetic have influenced records by Andrew Bird, Neko Case, Morphine and PJ Harvey.

As Waits’ acclaimed series of albums on Island Records from the ‘80s and ‘90s are being reissued in remastered form — some for the first time on vinyl in decades — GRAMMY.com revisits the legendary singer/songwriter’s significant body of work via each of his studio albums. Press play on the Spotify playlist below, or visit Apple Music, Pandora, and Amazon Music to enter Waits' sonic wonderland of '70s era ballads and his plethora of twisted narratives and experimental sounds.

The Barroom Balladeer

Though often treated to his own idiosyncratic filter, Waits’ early output in the ‘70s reflected the glamor and sleaze of his Los Angeles surroundings.

Closing Time (1973)

Making his debut at the height of the ‘70s singer/songwriter boom, Tom Waits revealed only slight glimpses of his myriad idiosyncrasies on 1973’s Closing Time. Heavily composed of ballads, the album’s sound is a result of a compromise between Waits’ own preference for more jazz-leaning material and producer Jerry Yester’s penchant for folk.

Despite, or perhaps because of, that creative tension, Closing Time has a unique character. A sense of wanderlust and escape within its 12 piano-based songs feels like a jazzier, West Coast counterpart to Bruce Springsteen. Waits imbues the call of the road with a sense of melancholy on gorgeous opener "Ol’ 55" and gives a hefty tug at the heartstrings on the aching "Martha." He kicks up the tempo on "Ice Cream Man." Closing Time is often at its best when it’s more quietly haunting, like on the bluesy "Virginia Avenue."

Though the album didn’t initially garner much critical or commercial attention, it’s since become regarded as one of the finest moments of Waits’ early recordings. It also quickly earned the respect and admiration of other artists, with various songs from Closing Time being covered by Bette Midler, Eagles and Tim Buckley.

The Heart of Saturday Night (1974)

After establishing himself with the romantic ballads of his debut album, Waits waded deeper into the waters of boho jazz and beat poetry in its follow-up, The Heart of Saturday Night.

Waits shares his perspective from the piano bench and the barstool, occasionally delving into a sing-speak delivery against upright bass and brushed-drum backing. Throughout, Waits serves up colorfully embellished imagery about nights on the town and getting soused on the moon. Though not as experimental or sophisticated as some of his later recordings, The Heart of Saturday Night nonetheless finds Waits in a more playful mood, more overtly showcasing his sense of humor and penchant for a particular kind of down-and-out protagonist. Fittingly, the album's title track was directly inspired by Jack Kerouac.

The Heart of Saturday Night is somewhat autobiographical in that it’s one of the few albums that repeatedly features references to his youth growing up in San Diego. Most famously on "San Diego Serenade," as well as in his narrative of driving through Oceanside in "Diamonds on My Windshield," and his name-drop of Napoleone’s Pizza House, the pizzeria in National City where he worked as a teenager, in "The Ghosts of Saturday Night."

Nighthawks at the Diner (1975)

As Tom Waits further established himself as a singer/songwriter more at home in the naugahyde and second-hand smoke of a seedy nightclub than a folk festival, he sought to replicate the atmosphere of a jazz club on his third album. It’s not a live album in a literal sense; Waits invited a small crowd into the Record Plant studio in Los Angeles on two nights in July of 1975, and though the venue is artifice, the crowd reactions are genuine.

More heavily rooted in jazz than Waits’ first two albums, Nighthawks at the Diner mostly follows a particular pattern: An "intro" track featuring some witty barfly banter, followed by an actual song. Introducing each song with a round of inebriated wordplay ("you’ve been standing on the corner of Fifth and Vermouth," "Well I order my veal cutlet, Christ, it just left the plate and walked down to the end of the counter…") is a bit of a gimmick, yet for all its loose, freewheeling feel, the album features some of his best early songs, including "Eggs and Sausage," "Warm Beer and Cold Women" and "Big Joe and Phantom 309."

Releasing a manufactured live album early on proved a canny gambit for Tom Waits and resulted in his highest charting album up to that date. And it’s easy to see why: Nighthawks showcased the raconteur persona that’d come to define much of Waits' work to come.

The Bluesy Bohemian

Embracing a grittier sound and a more character-driven approach to storytelling, Tom Waits entered a period of creative growth in the second half of the ‘70s that saw him balancing a darker tone with a wry sense of humor.

Small Change (1976)

On his second and third albums, a jazz influence and increasingly prominent humor saw Waits developing not just as a distinctive personality, but as a character. His raspy growl deepened onSmall Change, as Waits' barfly persona finds himself in increasingly seedier surroundings. This new area is best showcased through the amusingly unsexy striptease scat of "Pasties and a G-String" and the surreal and misty eyed "The Piano Has Been Drinking."

Small Change isn’t nearly as jokey as the previous year’s Nighthawks at the Diner, but Waits carries a persistent smirk as he rattles through a laundry list of hucksterish advertising slogans in the carnival-barker beat jazz of "Step Right Up": "It gets rid of unwanted facial hair, It gets rid of embarrassing age spots, It delivers the pizza." He even ramps up an element of danger in the noir poetry of "Small Change (Got Rained on With His Own .38)".

Still, the heartache and romance remains within the album’s best ballads, including the gorgeous opener "Tom Traubert’s Blues" and the imagined depiction of a lonely waitress in "Invitation to the Blues."

Foreign Affairs (1977)

Tom Waits’ fifth album Foreign Affairs unexpectedly became one of his most consequential releases.

A rare Waits album that opens with an instrumental ("Cinny’s Waltz"), Foreign Affairs finds him taking on more narrative driven songwriting, as in the lengthy noir tale of "Potter’s Field" and the nostalgic road-movie recollection of "Burma-Shave." It seems fitting that this is the moment where Hollywood began to crack a door open for Waits — these songs sound like they were made for the silver screen.

Indeed, album standout "I Never Talk to Strangers," a duet with Bette Midler, inspired Francis Ford Coppola’s 1981 film One From the Heart. Waits wrote and performed on its soundtrack, and would work with Coppola multiple times.

Blue Valentine (1978)

Parallels between Waits' music and his acting career crop up throughout , beginning with 1978’s Blue Valentine. Released the same year that he made his acting debut in Paradise Alley — cast as a piano player named Mumbles, an apt role to be sure — Blue Valentine opens with a big, cinematic number itself, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s "Somewhere," the famous ballad from West Side Story.

Blue Valentine also finds Waits in character development mode, increasingly populating his bluesy and bedraggled songs with widows and bounty hunters, night clerks and scarecrows wearing shades. It also features one of his most heartbreaking songs in "Christmas Card from a Hooker in Minneapolis," in which Waits’ first-person epistle comes from the voice of the title character who reaches out to an old friend in a hopeful and warm update on the changes she’s made for the better. And then he seamlessly, devastatingly pulls out the rug from underneath it all, as only a fabulist like Tom Waits can.

Heartattack and Vine (1980)

The transition from one decade to the next couldn’t have been starker for Tom Waits as he entered the 1980s. His final album for Asylum Records seemed to signal a sea change, with its leadoff track steeped in scuzzy, distorted guitar and gruff blues-rock rather than piano balladry, jazz and beat poetry.

Heartattack and Vine is in large part more of a proper rock record than any of Waits’ earlier albums, as he lends his husky growl to gritty songs such as "Downtown" and "In Shades." Still, it’s the most tender moments that comprise some of Heartattack and Vine’s most enduring songs, such as "On the Nickel" and, in particular, "Jersey Girl," covered four years later by the Garden State’s own Bruce Springsteen.

The Avant-Garde Auteur

Tom Waits underwent a significant transformation in the 1980s, mostly leaving behind the smoky jazz-club ballads of the ‘70s in favor of a more avant garde take on rock music, rife with an arsenal of unconventional instruments.

Swordfishtrombones (1983)

The most dramatic shift in Tom Waits’ career came with the release of 1983’s Swordfishtrombones, his first release for Island Records and the first album of what came to be the sound most often associated with Waits. It’s rougher, rawer, more experimental and offbeat. A great deal of the credit goes to Waits’ wife, Kathleen Brennan, who introduced him to artists like Captain Beefheart and who became his creative partner, co-writing many of his best-known songs.

Waits trades the piano and strings of his earlier material for arrangements better fit for junkyard jam sessions and New Orleans funerals. Though he’s delivered a long list of releases that have since usurped such a title, Swordfishtrombones certainly sounded like his weirdest album at the time. Very little of it sounded like a conventional pop song;it’s interwoven with spoken-word pieces both hilarious and unnerving ("Frank’s Wild Years," "Trouble’s Braids"), instrumentals ("Dave the Butcher," "Rainbirds"), boneyard bashers ("Underground," "16 Shells from a Thirty-Ought Six") and even a few tender ballads ("Johnsburg, Illinois," "Town With No Cheer").

Though arguably far less commercial than anything he’d released prior, Swordfishtrombones still cracked the bottom half of the album charts. It also received the attention of critics, who praised Waits’ bold new direction and unconventional stylistic choices.

Rain Dogs (1985)

For much of the 1970s, Tom Waits took inspiration from the seamier side of Los Angeles, with occasional sentimental nods to his youth further south along Interstate 5 in San Diego. With 1985’s Rain Dogs, however, he relocated to New York City to capture an even grimier and grittier album inspired by its outcasts and outlaws.

Recorded in what was then a rough part of Manhattan in 1984, Rain Dogs continues the stylistic experimentation of Swordfishtrombones with an unusual array of instruments for a rock album, including marimba, trombone and accordion, the latter of which opens the title track in dramatic fashion with an incredible solo.

Rain Dogs also began Waits’ long collaborative relationship with Marc Ribot, whose guitar playing helps craft the album's signature sound. Through his Cuban jazz-inspired playing on "Jockey Full of Bourbon" and the scratchy and dissonant solo on "Clap Hands." Yet the album also finds him in the company of Keith Richards, whose licks appear on the album’s most famous song, "Downtown Train," which became a hit for Rod Stewart when he covered it in 1991.

Rain Dogs features Waits’ first co-writing credit from Brennan, brought dded gravitas to the aching ballad "Hang Down Your Head." It’s one of a few moments that cuts through the carnivalesque atmosphere of the album (see the demented nursery rhyme "Cemetery Polka," the crime-scene poetry of "9th and Hennepin" and the litany of misfortunes in "Gun Street Girl"). IRain Dogs is Tom Waits perfecting his approach, completing a stylistic transformation with one of his greatest batches of songs.

Frank’s Wild Years (1987)

One of the highlights of Waits’ 1983 album Swordfishtrombones was a humorous spoken-word jazz interlude wrapped up in a David Lynch nightmare, titled "Frank’s Wild Years," in which the titular Frank settles down into a suburban lifestyle, only to set his house on fire and drive off with the flames reflecting in his rearview mirror. Those 115 seconds or so were enough for Waits and Brennan to spin the idea out into a stage play, with this album serving as its soundtrack. (Its original cast at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre included Gary Sinise and Laurie Metcalf.)

Frank’s Wild Years likewise comprises songs performed in the play, though without the context of knowing its origins, it doesn’t so easily scan as a set of songs written for the stage. It continues the aesthetic vision that Waits pursued on his two previous Island Records albums, steeped in Weill-ian cabaret and mangled lounge-jazz renditions, like in the hammy Vegas version of "Straight to the Top." Waits continues to run wild stylistically, however, veering from junkyard blues-rock in opener "Hang On St. Christopher" to the tenderness of the lo-fi 78-style recording of closing ballad "Innocent When You Dream."

Fifteen years after its release, "Way Down in the Hole," was given a second life as the theme for the HBO drama "The Wire," each season featuring a different artist’s rendition of the song. Waits’ original scores the opening credits for season two.

Bone Machine (1992)

The title of Tom Waits’ tenth album fairly accurately sums up the sound of the record, which finds Waits incorporating heavier use of curious forms of percussion, many of them he played himself. Opening track "Earth Died Screaming" even resembles the sound of bones clanking against each other as Waits growls his way through an apocalyptic nightmare.

It’s fitting that Bone Machine coincided with Waits’ appearance as Renfield in Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula. A macabre sensibility and grotesque narratives permeate this record:Acts of violence become a form of entertainment in "In the Colosseum," and he retells an actual story of a grisly homicide in "Murder in the Red Barn." There’s levity too, like in the delusions of a fame-seeker in the rowdy "Goin’ Out West," which, along with half the songs on the album, was co-written by Brennan.

Eerie and macabre as Bone Machine is, it earned Waits his first GRAMMYAward, for Best Alternative Music Album in 1993. Likewise, the Ramones covered standout track "I Don’t Wanna Grow Up" three years later on their final album ¡Adios Amigos!; Waits repaid the favor in 2003 with a cover of the band’s "Return of Jackie and Judy."

The Storyteller’s Songbook

Deeper into the ‘90s and ‘00s, Waits became more active in writing music for the theatrical stage, albeit filtered through his own peculiar lens. He also closed out the ‘90s with his longest album, helping to usher in a late-career renaissance.

The Black Rider (1993)

The soundtrack to a theatrical production,The Black Rider closed Waits' tenure with Island Records with the soundtrack to a theatrical production. Though his music appeared in films by the likes of Jim Jarmusch and Francis Ford Coppola, and he entered the world of theater with Frank’s Wild Years, this was his released composed in collaboration with playwright Robert Wilson — they would work on three productions together — based on German folktale Der Freischütz. In fact, Waits affects his best German accent in the title track, in which he beckons, "Come on along with ze black rider, we’ll have a gay old time!"

Highlights "Flash Pan Hunter," "November" and "Just the Right Bullets" juxtapose distorted barks against ramshackle arrangements of plucked banjo, clarinet and singing saw. , The structure of the album — rife with interludes, instrumentals and reprises — sets it apart from any of his prior works, leaving room for the listener to fill in the visual blanks.

Mule Variations (1999)

The release of Mule Variations coincided with the launch of Anti- Records, an offshoot of L.A. punk label Epitaph that was more focused on legacy artists in a variety of genres. This also resulted in the unlikely instance of a song by Tom Waits appearing on one of Epitaph’s famed Punk-O-Rama compilations, which typically featured selections by the likes of skatepunk icons NOFX and Pennywise.

The longest studio album in Waits’ catalog, Mule Variations makes good on a six-year gap by being stacked with an eclectic selection of songs, most of them co-written with Brennan (who also co-produced the album). From the lo-fi beatbox bark that blows open the doors of leadoff track "Big In Japan," Waits essentially takes a tour through a disparate but cohesive set of songs that feels like a career summary, from tent-revival blues ("Eyeball Kid"), to devastating balladry ("Georgia Lee") and rapturous gospel ("Come On Up to the House").

A new generation of TikTok users received an introduction to this album via a meme featuring the album’s "What’s He Building In There?", an eerie spoken-word track from the perspective of a paranoid, busybody neighbor that became an unlikely viral sensation.

Blood Money & Alice (2002)

Another collaboration with playwright/director Robert Wilson, Blood Money and Alice were released on the same day in 2002. Co-written by Brennan, both are the soundtracks to two plays, the former based on an unfinished Georg Büchner play Woyzeck and the latter an adaptation of Alice in Wonderland.

Blood Money is darker and harsher in tone, kicking off with the satirically pessimistic "Misery is the River of the World," and featuring highlights such as the obituary mambo of "Everything Goes to Hell" and the charmingly tender "All the World Is Green."

Alice — whose songs had been circulated for years in bootlegs in rougher form — is more subdued and strange, its gorgeously lush and haunting opening ballad an opening into a head-spinning world of Lewis Carroll surrealism and disorientation. "Kommienezuspadt" soundtracks White Rabbit hijinks through German narration and Raymond Scott machinations, "We’re All Mad Here" lends a slightly darker shadow to an uneasy tea party, and "Poor Edward" diverts slightly from Carroll canon to visit the story of Edward Mordrake, a man born with a face on the back of his head.

The Catalog Continues…

Though Waits hasn’t been quite as prolific in the past two decades as he had been from the ‘70s through the late ‘90s, he continued to refine and evolve his strange and uncanny sound, while sharing a triple-album’s worth of rare material that offered a wide view of his evolution over the prior two decades.

Real Gone (2004)

Waits maintained his prolific streak with the lengthy Real Gone, which featured 16 songs and spans nearly 70 minutes — just a hair shorter than his longest, Mule Variations. It’s also the rare Tom Waits album to feature no piano or organ, its melodies primarily provided via noisier guitar from Harry Cody, Larry Taylor and longtime collaborator Marc Ribot, along with contributions from Primus bassist Les Claypool and Waits’ own son, Casey, who provides percussion and turntable scratches.

Real Gone is, at its wildest, the most abrasive record in Waits’ catalog, clanging and clapping and clattering through uproarious standouts such as the supernatural mambo of "Hoist That Rag," the CB-radio squawk of "Shake It" and creepy-crawly stomp "Don’t Go Into That Barn," one of his better scary stories to tell in the dark. He leaves a little room to ease back on dirges like the haunting "How’s It Gonna End" and the subtly gorgeous "Green Grass," but every corner of the album is populated by outsized characters and ominous visions that seem larger than ever.

Orphans: Brawlers, Bawlers and Bastards (2006)

A career as long and fruitful as that of Tom Waits is bound to leave some material on the cutting room floor, the likes of which is compiled on the triple-disc set Orphans. Composed of non-album material that stretches all the way back to the 1980s, it’s divided into three distinctive themes: Brawlers, a disc of rowdier rock ‘n’ roll and blues material; Bawlers, a set of ballads; and Bastards, made up of what doesn’t fit into the other two categories — essentially Waits’ most fringe, peculiar music.

In drawing the focus toward each distinctive type of songs, Waits lets listeners experience more intensive, discrete aspects of his music. It’s the "Bastards," however, that tap into the extremes of Waits’ unique talents, comprising strange and macabre storytelling, unintelligible barks, even a wildly distinctive take on "Heigh Ho," from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Some of these songs had previously been released in some fashion — many of them appearing on movie soundtracks as well as collaborative efforts like Sparklehorse’s "Dog Door" — Orphans speaks to how productive he’s been over the past 40 years.

Bad As Me (2011)

Tom Waits’ final album (so far) hit shelves 12 years ago, the aftermath of which opened up his longest stretch without any new music since he began releasing records. Yet Bad As Me only offers the suggestion that Waits still has plenty of energy and inspiration left in the tank, as the album — released when he was 61 years old — comprises some of the hardest rocking material he’s ever committed to tape. It’s an album heavy on rowdy rock ‘n’ roll guitar, including that of Keith Richards, who had also previously lent his guitar playing to 1985’s Rain Dogs, as well as longtime collaborator Marc Ribot and Los Lobos’ David Hidalgo. Waits mostly adheres to concise, charged-up barnburners such as "Let’s Get Lost," "Chicago" and the more politically charged anti-war song "Hell Broke Luce." Though when Waits does ease off the throttle on songs like the eerie "Talking at the Same Time," the results are often spectacular.

If Tom Waits were to simply leave this as the end of his recorded legacy, it’d be a satisfying closing statement, though the closing ballad "New Year’s Eve" — ending on a brief round of "Auld Lang Syne" — would suggest new beginnings ahead of him. As it turns out, Bad As Me isn’t intended to be his last; earlier this year he confirmed that, for the first time in over a decade, he’s been working on writing new songs.

Songbook: A Guide To Wilco’s Discography, From Alt-Country To Boundary-Shattering Experiments