Graphic House/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Mary Lou Williams

news

Listen: Close Out Jazz Appreciation Month 2021 With GRAMMY.com's Playlist - 40 Tunes For The Rest Of The Year

Jazz Appreciation Month may be wrapping up, but listeners can bring that energy into the rest of the year—one where the music needs our support more than ever

It's International Jazz Day, but many of its greatest musicians haven't worked in more than a year. Jazz Instagram is a cornucopia of hawked Zoom masterclasses. Many of the most beloved, irreplaceable physical spaces are gone—possibly forever.

What's the answer to getting more listeners on board? Maybe it's to make it less of a history lesson—and communicate that you can turn up Charlie Parker next to your favorite rock, rap or R&B song. You don't need accreditation. You don't need a college degree. You don't need to read a manual. It just sounds good.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://open.spotify.com/embed/playlist/1f7g7D9f0SpJNJZuRNjexn' width='300' height='380' frameborder='0' allowtransparency='true' allow='encrypted-media'></iframe></div>

GRAMMY.com is closing out Jazz Appreciation Month with a playlist of 40 tunes to bring into the rest of 2021. It's not meant to be remotely comprehensive; how could a playlist without Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, Billie Holiday, Count Basie, Louis Armstrong or the Art Ensemble of Chicago possibly be? Ignoring time and space in favor of (hopefully) uninterrupted enjoyment, it's simply the product of one unbroken train of thought.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe allow='autoplay *; encrypted-media *; fullscreen *' frameborder='0' height='450' style='width:100%;max-width:660px;overflow:hidden;background:transparent;' sandbox='allow-forms allow-popups allow-same-origin allow-scripts allow-storage-access-by-user-activation allow-top-navigation-by-user-activation' src='https://embed.music.apple.com/us/playlist/jazz-appreciation-month-2021/pl.u-BNA66Gbt1Voklv4'></iframe></div>

Check out the annotations below, and you might get a sense of how one track connects to the next—whether by the musicians involved, the historical context or simply the vibe. But that's it. If you want to dig deeper, there are countless books, websites and documentaries on offer. But maybe simply enjoying the music is the first step.

GRAMMY.com's Jazz Appreciation Month 2021 playlist is available here via Spotify, Amazon Music and Apple Music. If you like any of the tunes below, click the album title to buy the record and support them or their estate directly.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe id='AmazonMusicEmbeda7bbfcb5b7a548c39c26191f657ed24fsune' src='https://music.amazon.com/embed/a7bbfcb5b7a548c39c26191f657ed24fsune/?id=zmKvobczA8&marketplaceId=ATVPDKIKX0DER&musicTerritory=US' width='100%' height='550px' style='border:1px solid rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.12);max-width:'></iframe></div>

Without further ado, let's enjoy the music.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//DmRkZeGFONg' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Charlie Parker, "Just Friends" (Charlie Parker With Strings, 1950)

In some ways, this is the only place to start. The greatest saxophonist of all time plays an improvised solo of jaw-dropping elegance, intelligence and integrity. "It's absolutely perfect on both an artistic and technical level," alto saxophonist Jim Snidero told Discogs in 2020.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//Liy9tw03p1I' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Lou Donaldson, "Blues Walk" (Blues Walk, 1958)

The alto saxophonist got friction early on for sounding too much like Parker, but more than carved out his own sound with masterpieces like "Blues Walk." At 94, Sweet Poppa Lou is still kicking—and totally cops to the associations. "I'm a copy of Charlie Parker," he said in the same article.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//cyAg5mFZOjQ' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Champian Fulton, "My Old Flame" (Birdsong, 2020)

Who played the most beautiful version of "My Old Flame" the world ever heard? That's right, Bird's your man—and the exquisite jazz singer Champian Fulton knows it. She's a fan of both Donaldson and Parker; her recent album Birdsong is a luminous tribute to the latter.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//Ho6Z816Hm6M' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Jim Snidero, "Autumn Leaves" (Live at the Deer Head Inn, 2021)

After months of no gigs during the COVID-19 pandemic, Snidero and his quartet played safely and socially distanced at a jazz hotspot in the Delaware Water Gap. Despite the low-key setting and setlist of standards, he showed that chestnuts like "My Old Flame" "Autumn Leaves" still have new dimensions to explore.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//-J5Qo1eCQ6A' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Helen Sung, "Crazy, He Calls Me" ((re)Conception, 2011)

Pianist Helen Sung is connected to Snidero by at least two degrees: she and bassist Peter Washington have both played with him. Her entire body of work is worth spending time with; 2018's Sung With Words is an exceptionally well-done merging of jazz and poetry.''

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//hYbLEjyrLZc' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Cannonball Adderley, "One For Daddy-O" (Somethin' Else, 1958)

Make no mistake: alto man Cannonball's only Blue Note album is a drop-dead must-have album. "Is that what you wanted, Alfred?" his sideman, Miles Davis, growls at producer Alfred Lion at the end of "One For Daddy-O." (Certainly, it was.)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//ZZcuSBouhVA' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Miles Davis, "Freddie Freeloader" (Kind of Blue, 1959)

Er, you want this album too. Trust us.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//JMOjyZtNxX8' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Wes Montgomery, "If You Could See Me Now" (Smokin' at the Half Note, 1965)

Jimmy Cobb, who sadly left us in 2020, was the drummer on Kind of Blue, and you could set an atomic clock to his ride-cymbal hand. Cobb also plays on this Wes Montgomery masterpiece. Even though Montgomery couldn't read music and strummed exclusively with his thumb, he arguably remains the king of jazz guitarists.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//qGF7873UxTw' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Bill Evans & Jim Hall, "Skating in Central Park" (Undercurrent, 1962)

Well, actually, it's either him or Jim Hall. (The ever-ethereal melodist Evans is also in the running for Kind of Blue MVP.)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//NWCkC7TRd1k' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Julian Lage, "Boo's Blues" (Squint, 2021)

Lage not only played with Jim Hall; the jazz world widely regards him as the Jim Hall of our generation. Not bad for a 33-year-old.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//d6gWjr0rQ1o' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Pat Metheny, "Missouri Uncompromised" (Bright Size Life, 1976)

The guitar genius arguably made even better records than Bright Size Life, but as an entryway to his approach and thinking, nothing beats his ECM Records debut. (On bass: Jaco Pastorius!)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//aq0m0hbCjFQ' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Grant Green, "Idle Moments" (Idle Moments, 1964)

Another guitar god, playing his pianist Duke Pearson's slow-crawling masterpiece. The musicians were unclear as to whether each chorus should be 16 or 32 bars, thereby beautifully blurring the composition. The results are a must-play for your next long drive and long think.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//svPr2x1OpDQ' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Miguel Zenón & Luis Perdomo, "Cómo Fue" (El Arte del Bolero, 2021)

Or, "The art of the bolero," or, "Two guys soothing themselves during lockdown with traditional songs they've known all their lives." Despite its low-key presentation—it was a Jazz Gallery livestream the altoist and pianist decided to record—this was one of the most captivating duo records in recent memory.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//DXLKnHua7aI' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Avishai Cohen & Yonathan Avishai, "Crescent" (Playing the Room, 2019)

ECM comes up for a reason; if you're not familiar with the ultra-prolific label, go to their website, find something with a blanket of snow or raindrops on windows as the cover, and chances are it's drop-dead gorgeous. And speaking of stellar duet albums, here's another, between the Tel Aviv-born trumpeter and the Israeli-French pianist.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//pdhqHUem2FE' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Craig Taborn, "Abandoned Reminder" (Daylight Ghosts, 2017)

Deeper we tread into the realm of ECM: Everything this brilliant pianist has made is worth hearing at least once. (Especially his Junk Magic project's latest album, Compass Confusion, which is not ECM and not jazz but is terrifying.)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//6lzgOHbdGWs' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Vijay Iyer Trio, "Combat Breathing" (Uneasy, 2021)

The Harvard professor and pianist surveys the volatile landscape of 2021 with the radiant rhythm section of bassist Linda May Han Oh and drummer Tyshawn Sorey. (GRAMMY.com cited both Oh and Sorey as artists pushing jazz into the future.)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//z6Sg1dIjKRw' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Linda May Han Oh, "Speech Impediment" (Walk Against Wind, 2017)

One of the most prodigious modern bassists and composers, Oh made GRAMMY.com's list of five jazz artists pushing the form into the future. That's her on the Iyer tune, too, along with the drummer and composer Tyshawn Sorey.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//adegtCnTTOo' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Geri Allen Trio, "Eric" (The Printmakers, 1984)

Everybody should know this brilliant pianist and composer; Iyer is possibly the most prominent figure promoting her work these days. (He recently wrote an academic paper about Allen; "Drummer's Song" from Uneasy is hers.)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//jEc-r89co6Q' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Mary Lou Williams, "My Blue Heaven" (Black Christ of the Andes, 1964)

In a just world, we'd regularly breathe Mary Lou Williams' name along with Ellington's and Armstrong's and her multidimensional masterpiece Black Christ of the Andes would be taught in schools.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//jOkBpSItuP8' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Alice Coltrane, "Turiya and Ramakrishna" (Ptah, the El Daoud, 1970)

In recent years, Coltrane has received wildly overdue reappraisal as her husband John's artistic equal. Still, only one album has seemingly been allowed into the canon: Journey in Satchidananda. But as more than a dozen musicians attested to GRAMMY.com in 2020, Ptah deserves a seat at the table, too.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//C_p79u6xJUU' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Lakecia Benjamin, "Syeeda's Song Flute" (Pursuance: The Coltranes, 2020)

Understanding that fundamental truth about the Coltranes, alto saxophonist Benjamin made the communal and devotional Pursuance: The Coltranes, which pays homage to both artists equally. (This is a John tune, but she found Alice before him.)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//lJf-8uJ9TIs' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

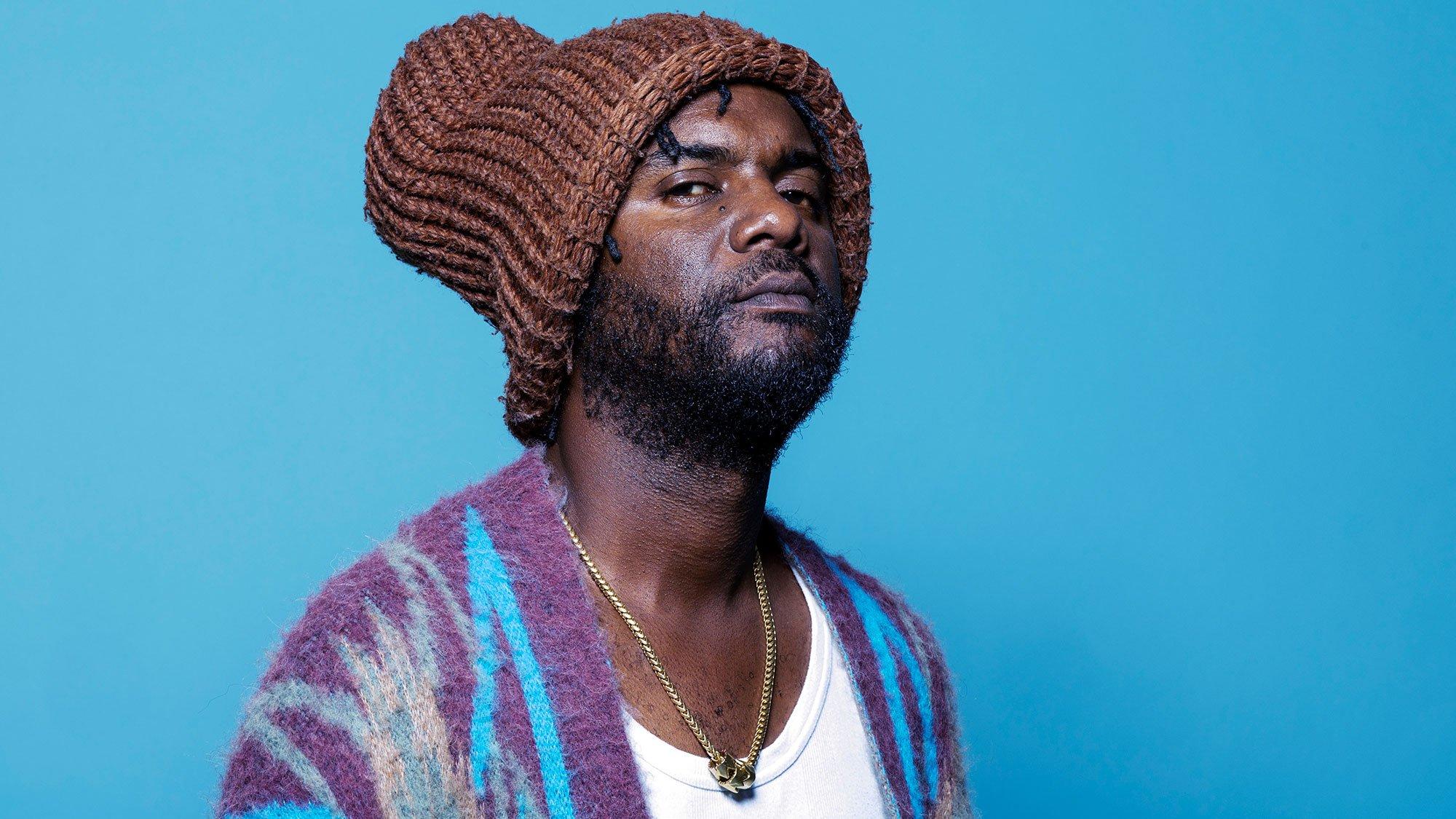

- Keyon Harrold, "Bubba Rides Again" (The Mugician, 2017)

The celebrated trumpeter Harrold shows up to jam on Benjamin's album, and his album The Mugician is a terrific gateway into the crossover world where jazz, rap and R&B blur.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//vhYVSXz7bx8' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Kassa Overall, "Please Don't Kill Me" (I Think I'm Good, 2020)

Speaking of crossover: Kassa Overall is one of that sphere's very best. Understanding that jazz and rap are more similar than dissimilar, he opts not to blur them but crash them like cars, knowing the wreckage will look the same.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//BSc6E-a2EEs' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Joel Ross, "More?" (Who Are You?, 2020)

This sublime vibraphonist (who appears on the previous Overall tune) is right on the front lines of the scene in 2021. Don't sleep on him or his elegant last album, Who Are You?.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//wgKXUYfXxXw' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Jackie McLean, "'Das Dat" (It's Time!, 1964)

But if you really want to get into the heritage of jazz vibraphone, Bobby Hutcherson is the first man to know. Check out his performance on alto sax heavyweight J-Mac's It's Time!, which got an excellent pressing last year via Blue Note's Tone Poet Series.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//c8fvOJvRmPY' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Bobby Hutcherson, "Maiden Voyage" (Happenings, 1966)

Here he is again, performing Herbie Hancock's intoxicating tune with Hancock himself. (For Hancock's part, he's one of the most inventive harmonic thinkers of the 20th and 21st centuries.)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//8birZZ2pye0' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Joey Alexander, "Under the Sun" (single, 2021)

The astonishing young pianist Joey Alexander met Hancock at the GRAMMYs when he was only eight. "He didn't say too much," he recalled to GRAMMY.com in 2021. "He thought I could play and he said, 'Keep doing it' and 'Don't stop.'"

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//9xuKtzZ6FVI' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Jaleel Shaw, "The Flipside" (Optimism, 2008)

A.n excellent alto saxophonist, Shaw appears on Alexander's previous single, "SALT." "I was glad that Jaleel and [guitarist] Gilad [Hekselman] played in unison and sounded so strong," Alexander marveled in the same interview. "When I heard it back, I was like 'Wow.'"

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//CrUm4CsKW8c' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Rudresh Mahanthappa, "I Can't Get Started" (Hero Trio, 2020)

On an alto-saxophone kick? Mahanthappa has one of the boldest, brashest and most vibrant sounds on the instrument in 2021.

- Matthew Shipp, "Swing Note from Deep Space" (The Piano Equation, 2020)

Now, we shift gears to the solo piano; Shipp is one of the most prodigious modern improvisers in that realm. (The label that released The Piano Equation, TAO Forms, is one of GRAMMY.com's labels to watch in 2021.)

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//goDL6GcYPEo' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Thelonious Monk, "Don't Blame Me" (Palo Alto, 2020)

More than a half-century ago, Monk played at a high school and a janitor recorded it. Nobody heard the slamming results until Impulse! released them in 2020.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//r2y5s-c1mjw' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Oscar Peterson & Dizzy Gillespie, "Dizzy Atmosphere" (Oscar Peterson & Dizzy Gillespie, 1974)

These days, the "bebop" pioneer Diz might be more revered and analyzed than listened to. But he was a tremendous trumpeter throughout all seasons of his life—as attested to by this duo album with piano giant Oscar Peterson.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//OQezPrCyhNU' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Dave Douglas, "Pickin' the Cabbage" (Dizzy Atmosphere, 2020)

Need further proof? Check out the ultra-prolific Douglas' loving tribute to the clown prince of jazz.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//k-Qao6K_jIQ' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Jakob Bro Trio, "Copenhagen" (Bay of Rainbows, 2018)

The connection to the Douglas album is the ultra-perceptive drummer Joey Baron. Danish guitarist Bro's sets at Jazz Standard (before they shuttered their physical location thanks to COVID) were transformative experiences, as captured on this ECM recording from the New York venue.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//S4ylZmsR8AM' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, "A Night in Tunisia" (A Night in Tunisia, 1961)

Honestly, it just felt right to blow up the program in a volley of toms.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//FcwhoDvE3YY' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Sonny Rollins, "Tune Up" (Rollins in Holland, 2020)

We're at the final stretch. Newk killing on a Netherlands tour.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//PttNMqbNMOI' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- John Coltrane, "Mr. P.C." (Giant Steps, 1960)

"P.C." is bassist Paul Chambers, who left us too young. That's all the backstory you need. Turn this up like a Led Zeppelin song.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//G7IT0eRl79g' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Ralph Peterson, "Freight Train" (The Art of War, 2001)

Rest in power to Peterson, a ferocious drummer and sweetheart of a man who left us in 2021. Last year, he summed up his mentor, Art Blakey: "He's in the blue part of the flame," Peterson told GRAMMY.com. "The thing is: if you know anything about fire, the blue part of the flame might be the lowest part of the flame, but it's also the hottest part of the flame."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//TJxURT1NGro' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Bill Frisell, "We Shall Overcome" (Valentine, 2020)

Now, we turn down the burner. "I'm going to play it until there's no need anymore," Frisell said in a statement about this civil-rights anthem.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//7AdImz8wz0E' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

- Oded Tzur, "Can't Help Falling in Love" (Here Be Dragons, 2020)

End credits.

Surrounded By Moving Air: 6 Big-Band Composers Pushing The Format Forward

Photo: Eduardo Reyes Aranzaez

feature

At Getting Funky In Havana, Young Musicians Feel The Power Of Cross-Cultural Connection

An annual program organized by the Trombone Shorty Foundation and Cimafunk, Getting Funky In Havana explores the deep connections between Cuba and New Orleans — and provides student musicians with once-in-a-life-time learning opportunities.

It’s sweltering inside the Guillermo Tomas Music Conservatory, a primary school in Havana’s Guanabacoa neighborhood, where American visitors enjoy what will likely be the best school recital they'll ever see.

A series of teen and tween musicians — some in trios and quartets, others in larger ensembles — are playing a mix of Latin jazz, orchestral overtures and even a rousing rendition of the Ghostbusters theme. During an interpolation of Aretha Franklin's "Think," three young horn players burst to the front of the group in a competitive but friendly battle of brass.

The performance is the centerpiece of Getting Funky in Havana, a four-day music and cultural exchange program developed by GRAMMY-nominated Cuban funk artist Cimafunk, GRAMMY-winning New Orleans multi-instrumentalist Trombone Shorty's namesake foundation, and Cuba Educational Travel. Now in its third year, Getting Funky brought nearly 200 American music lovers, artists and students to Havana in January to explore the deep connections between Cuban and New Orlenian sounds through a series of performances, educational activities and panels.

"Cuba and New Orleans have a long line of influence, and we have special things that happen in both places that people can hear through our music," Trombone Shorty, born Troy Andrews, tells GRAMMY.com. "Passing along music and knowledge is…how the music's staying alive. I always try to tell the kids, learn everything that came before you, but also be very innovative."

While there are many conservatories in Havana, Guillermo Tomas was chosen in part for its similarities to New Orleans' Treme neighborhood, where many of the Trombone Shorty Foundation students live. Guanabacoa is "probably the deepest Afro-Cuban cultural neighborhood" in Havana, says Foundation Executive Director Bill Taylor.

Those shared roots and experiences were on display during several capstone concerts, which were also open to Havana residents. At a massive outdoor concert blocks away from Havana's famous Malecón, Getting Funky attendees enjoyed performances from Cuban salsa legends Los Van Van, reparto star Wampi and Shorty's Orleans Avenue. At a pinnacle performance the day before, more than 30 artists gathered at Havana arts hub La Fabrica for a sold-out international jam. Shorty, Big Freedia, Ivan Neville, percussionist Pedrito Martinez, PJ Morton, Tarriona "Tank" Ball, drummer Yissy Garcia and others joined forces with Cuban artists Reina y Real and X Alfonzo to create an unceasing groove.

Cuban and American students perform outside Guillermo Tomas┃Eduardo Reyes Aranzaez

While the concerts certainly brought the energy to a fever pitch, the beating heart of Getting Funky is its mission of music education. Ten members of the Trombone Shorty Foundation's brass band traveled to Cuba, where they performed at Getting Funky's opening night party and several other events. Throughout the week, the New Orleans students shared stages with their Cuban counterparts, learning each others' musical idioms and finding common ground.

"So much of the music [we hear in New Orleans comes] from Africa through the Caribbean to New Orleans, then spreading throughout the United States. When our students connect with those [Cuban] students, there's a natural, symbiotic connection that takes place," Taylor says.

High school senior and sax player Dylan Racine called the trip — his first time out of the country — a life-changing experience. "I learned so many new skills on this trip, including how to network, how to collaborate with young people from a different culture than me, and more," he says via email. Drummer and pianist John Rhodes, another senior, added that the experience was invaluable.

"I was able to interact with another culture and understand other young people through music. Although we couldn't speak the same language, we understood each other musically," he writes.

Both Cuba and New Orleans' unique musical cultures require constant innovation to survive, Taylor adds. "You honor the past, but it needs an infusion of new life in order to thrive. Getting Cuban musicians together with New Orleans musicians infuses a shot of energy into both of those musical styles."

The trip also put students from both countries in contact with working musicians, whose own perspectives were expanded by the experience.

"Music education and pedagogical expertise is so important. We need the next level to come up and be dope, just like we are," says trumpeter Keyon Harrold, whose work has taken him from sessions with Beyoncé to the 2024 GRAMMYs. This was Harrold’s second year at Getting Funky. "It's even more visceral and engaging to actually see these kids at the age of 10, 11, 12, and to know that in five years they're going to be the next."

For many of the musicians who attended, Getting Funky was an inspirational experience that furthered their existing work as well. "I perform for a living, but performing and playing with [students] is super dope. [Their energy is] clean," says GRAMMY-winning producer, rapper and mentor Deezle. "If I can in any way help to guide their path away from the pitfalls that I've encountered and endured, I would love to do that."

Legendary singer/songwriter Ivan Neville said he was blown away while watching young musicians from different worlds performing together. "This music was making their souls feel so good. I know music is good for the soul, but it was another level that I saw."

Fabio Daniel (center) and members of Primera Linea, or "first line"┃Eduardo Reyes Aranzaez

Since Getting Funky In Havana was established in 2020, the program has had a measurable impact on Cuban students' lives. In 2023, several young Cuban musicians traveled to New Orleans during JazzFest, where they visited Shorty’s studio and performed together at legendary venue Tipitina's. When the group returned home, they formed their own brass band, Primera Linea.

"This band is working; they are playing many places in Havana and that's thanks to the project. They were so into the satisfaction of [feeling] that they are valued," says Erik Alejandro Iglesias Rodríguez, who records as Cimafunk. "They are learning good quality things in terms of human relationships and in terms of music. [The program is] something that changes their mentality and lets them know that they can make it."

While Cuba harbors an incredible amount of musical talent, "making it" as a musician in the country comes with a unique set of challenges. The country's shrinking economy, high rate of inflation and low monthly incomes have 62 percent of Cubans reporting that they "struggle to survive" financially, according to a 2023 survey. Purchasing a professional calibur instrument, which may cost hundreds or thousands of U.S. dollars, often comes with great sacrifice.

It's an emotional day back at the Guillermo Tomas, where 10 of the school's top students will be awarded an instrument.

"An instrument is not something you can buy in a store," says Amanda Colina González, an art historian and one of the trip guides, who studied saxophone in conservatory. Colina González, like the majority of students, was given an instrument to play for the duration of her studies but had to return it to her school upon graduation. Remembering that moment brought tears to her eyes.

Because of its high cost and the possibility of leading to international travel, owning their own instrument can truly change a young musician's life. Getting Funky has donated approximately 50 instruments to Cuban students over three years of programming.

Fifteen-year-old Daniela Hernandez was awarded a trombone for her skill and dedication to music outside of school. Harried and teary-eyed after the recital, she shared her happiness and pride for being able to play with musicians who she's long admired. She plans to use her new trombone to study and will "take it with me everywhere."

Daniela and classmate Fabio Daniel (who received a trumpet during the first edition of Getting Funky in Havana in 2020) joined Trombone Shorty onstage at Getting Funky, performing for more than 15,000 people. Several of their friends and classmates brought their instruments to the concert — the largest held in Cuba in the last four years — and played back at the band from the crowd.

"Cuban musicians really enjoy playing and making other people feel joy through music,” Daniela says. Fellow trombone player and awardee Cristian Onel León says it's important to play for people outside of Cuba, and enjoys teaching people about his country's rhythms and keys. "I’m [also] learning other forms of playing, that aren’t mine. And it feels good,” he adds.

The program's instrument donation is spearheaded by the long-running nonprofit Horns To Havana, and supported by the Gia Maione Prima Foundation and private donors. Tickets purchased to attend the program also fund its efforts; Taylor says 2024's Getting Funky raised approximately $50,000. The Trombone Shorty Foundation hopes to continue the annual event, and expand into different countries; a 2025 Havana trip is already in the works.

For Rodríguez, who recently moved to New Orleans, the effect of this musical exchange is tangible. He's noticed more musicians who are open to collaborating across borders, and is working on new music with artists who have attended Getting Funky in previous years.

"Just jamming changes everything," he says. "That changes the minds of people; that changes the sound."

The connections made during Getting Funky have led to a variety of opportunities for students on both sides of the Gulf of Mexico. Foundation alto saxophonist Jacob Jones credits the trip for broadening his way of thinking while playing music; Deezle says he wants to get Cuban trumpeter and bandleader Fabio Daniel on a track; Primera Linea may perform at San Francisco's Outside Lands festival in August.

"To be able to facilitate that, and give to these young musicians of Cuba, is unbelievable," Andrews says of the program. "It's just a blessing to be able to be a blessing and help out the next generation, and help those musicians see a brighter future."

Photo: Mike Miller

interview

Gary Clark, Jr. On 'JPEG RAW': How A Lockdown Jam Session, Bagpipes & Musical Manipulation Led To His Most Eclectic Album Yet

Gary Clark, Jr.'s latest record, 'JPEG RAW,' is an evolution in the GRAMMY-winning singer and guitarist's already eclectic sound. Clark shares the process behind his new record, which features everything from African chants to a duet with Stevie Wonder.

Stevie Wonder once said "you can’t base your life on people’s expectations." It’s something guitarist and singer Gary Clark, Jr. has taken to heart as he’s built his own career.

"You’ve got to find your own thing," Clark tells GRAMMY.com.

Clark recently duetted with Wonder on "What About The Children," a song on his forthcoming album. Out March 22, JPEG RAW sees Clark continue to evolve with a mixtape-like kaleidoscope of sounds.

Over the years, Clark has ventured into rock, R&B, hip-hop blues, soul, and country. JPEG RAW is the next step in Clark's eclectic sound and sensibility, the result of a free-flowing jam session held during COVID-19 lockdown. Clark and his bandmates found freedom in not having a set path, adding elements of traditional African music and chants, electronic music, and jazz into the milieu.

"We just kind of took it upon ourselves to find our own way and inspire ourselves," says Clark, a four-time GRAMMY winner. "And that was just putting our heads together and making music that we collectively felt was good and we liked, music we wanted to listen to again."

The creation process was simultaneously freeing and scary.

"It was a little of the unknown and then a sense of hope, but also after there was acceptance and then it was freeing. I was like, all right, well, I guess we’re just doing this," Clark recalls. "It was an emotional, mental rollercoaster at that time, but it was great to have these guys to navigate through it and create something in the midst of it."

JPEG RAW is also deeply personal, with lyrics reflecting on the future for Clark himself, his family, and others around the globe. While Clark has long reflected on political and social uncertainties, his new release widens the lens. Songs like "Habits" examine a universal humanity in his desire to avoid bad habits, while "Maktub" details life's common struggles and hopes.

Clark and his band were aided in their pursuit by longtime collaborator and co-producer Jacob Sciba and a wide array of collaborators. Clark’s prolific streak of collaborations continued, with the album also featuring funk master George Clinton, electronic R&B/alt-pop artist Naala, session trumpeter Keyon Harrold, and Clark’s sisters Shanan, Shawn, and Savannah. He also sampled songs by Thelonious Monk and Sonny Boy Williamson.

Clark has also remained busy as an actor (he played American blues legend Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup in Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis) and as a music ambassador (he was the Music Director for the 23rd Annual Mark Twain Prize for American Humor).

GRAMMY.com recently caught up with Clark, who will kick off his U.S. tour May 8, about his inspirations for JPEG RAW, collaborating with legendary musicians, and how creating music for a film helped give him a boost of confidence in the studio.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

You incorporated traditional African music on JPEG RAW. How did it affect your songwriting process?

Well, I think traveling is how it affected my songwriting process. I was over in London, and we played a show with Songhoy Blues, and I was immediately influenced. I was like, "dang, these are my musical brothers from all the way across the world."

I always kind of listened to West African funk and all that kind of stuff. So, I was just listening to that in the studio, and just kind of started messing around with the thing. And that just kind of evolved from there. I was later told by Jacob Sciba that he was playing that music trying to brainwash me into leaning more in that direction. I thought we were just genuinely having a good time exploring music together, and he was trying to manipulate me. [Laughs.]

I quit caring about what people thought about me wanting to be a certain thing. I think that being compared to Jimi Hendrix is a blessing and a curse for me because I'm not that. I will never be that. I never wanted to imitate or copy that, no disrespect.

You’ve got to find your own thing. And my own thing is incorporating all the styles of music that I love, that I grew up on, and [was] influenced by as a pre-teen/teenager. To stay in one space and just be content doing that has never been my personality ever…I do what I like.

I read that you play trumpet at home and also have a set of bagpipes, just in case the mood strikes.

I used to go collect instruments and old cameras from thrift stores and vintage shops and flea markets. So, I saw some bagpipes and I just picked them up. I've got a couple of violins. I don't play well at all — if you could consider that even playing. I've got trumpet, saxophone, flutes, all kinds of stuff just in case I can use these instruments in a way that'll make me think differently about music. It'll inspire me to go in a different direction that I've maybe never explored before, or I can translate some of that into playing guitar.

One of my favorite guitarists, Albert Collins, was really inspired by horn players. So, if you can understand that and apply that to your number one instrument, maybe it could affect you.

Given recent discussions about advancements in AI and our general inundation with technology, the title of your album is very relevant. What about people seeing life through that filter concerns you? Why does the descriptor seem apt?

During the pandemic, since I wasn't out in the world, I was on my phone and the information I was getting was through whatever social media platforms and what was going on in certain news outlets, all the news outlets. I'm just paying attention and I'm just like, man, there's devastation.

I realized that I don't have to let it affect me. Just because things are accessible doesn't mean that you need to [access them]. It just made me think that I needed to do less of this and more of being appreciative of my world that's right in front of me, because right now it is really beautiful.

You’ve said the album plays out like a film, with a wide range of emotions throughout. What was it like seeing the album have that film-like quality?

I had conversations with the band, and I'd expressed to them that I want to be able to see it. I want to be able to see it on film, not just hear it. Keyboardist Jon Deas is great with [creating a] sonic palate and serving a mood along with [Eric] "King" Zapata who plays [rhythm] guitar. What he does with the guitar, it serves up a mood to you. You automatically see a color, you see a set design or something, and I just said, "Let's explore that. Let's make these things as dense as possible. Let's go like Hans Zimmer meets John Lee Hooker. Let's just make big songs that kind of tell some sort of a story."

Also, we were stuck to our own devices, so we had to use our imagination. There was time, there was no schedule. So, we were free, open space, blank canvas.

The album opens with "Maktub," which is the Arabic word for fate or destiny. How has looking at different traditions given you added clarity with looking at what's happening here in the U.S.?

I was sitting in the studio with Jacob Sciba and my friend Sama'an Ashrawi and we were talking about the history of the blues. And then we started talking about the real history of the blues, not just in its American form, in an evolution back to Africa. You listen to a song like "Maktub," and then you listen to a song like, "Baby What You Want Me to Do" by Jimmy Reed….

The last record was This Land, but what about the whole world? What about not just focusing on this, but what else is going on out there? And we drew from these influences. We talked about family, we talked about culture, we talked about tradition, we talked about everything. And it's like, let's make it inclusive, build the people up. Let's build ourselves up. It’s not just about your small world, it’s about everybody’s feelings. Sometimes they're dealt with injustice and devastation everywhere, but there's also this global sense of hope. So, I just wanted to have a song that had the sentiment of that.

I really enjoyed the song’s hopeful message of trying to move forward.

Obviously, things are a little bit funky around here, and I don't have any answers. But maybe if we got our heads together and brainstorm, we could all figure something out instead of … struggling or suffering in silence. It's like, let's find some light here.

But part of the talks that I had with Sama'an and his parents over a [video] call was music. He’s from Palestine, and growing up music was a way to connect. Music was a way to find happiness in a place where that wasn't an everyday convenience, and that was really powerful. That music is what brought folks together and brought joy and built a community and a common way of thinking globally. They were listening to music from all over the world, American music, rock music, and that was an influence.

The final song on the album, "Habits," sounds like it was the most challenging song to put together. What did you learn from putting that song together?

Well, that song originally was a bunch of different pieces, and I thought that they were different songs, and I was singing the different parts to them, and then I decided to put them all together. I think I was afraid to put them all together because we were like, "let's not do these long self-indulgent pieces of music. Let's keep it cool." But once I put these parts together and put these lyrics together, it just kind of made sense.

I got emotional when I was singing it, and I was like, This is part of using this as an outlet for the things that are going on in life. We went and recorded it in Nashville with Mike Elizondo and his amazing crew, and it's like, yep, we're doing it all nine minutes of it.

You collaborated with a bunch of musicians on this album, including Naala on "This Is Who We Are." What was that experience like?

Working with Naala was great. That song was following me around for a couple of years, and I knew what I wanted it to sound like, but I didn't know how I was going to sing it. I had already laid the musical bed, and I think it was one of the last songs that we recorded vocals on for the album.

Lyrically, it’s like a knight in shining armor or a samurai, and there's fire and there's war, and this guy's got to go find something. It was like this medieval fairytale type thing that I had in my head. Naala really helped lyrically guide me in a way that told that story, but was a little more personal and a little more vulnerable. I was about to give up on that song until she showed up in the studio.

"What About the Children" is based on a demo that you got from Stevie Wonder. You got to duet with him, what was that collaboration like?

Oh, it was great. It was a life-changing experience. The guy's the greatest in everything, he was sweet, the most talented, hardworking, gracious, humble, but strong human being I've been in a room with and been able to create with.

I was in shock when I left the studio at how powerful that was and how game changing and eye-opening it was. It was educational and inspiring. It was like before Stevie and after Stevie.

I imagine it was also extra special getting to have your sisters on the album.

Absolutely. We got to sing with Stevie Wonder; we used to grow up listening to George Clinton. They've stuck with us throughout my whole life. So, to be able to work with him and George Clinton — they came in wanting to do the work, hardworking, badass, nice, funny — it was a dream.

Stevie Wonder and George Clinton are just different. They're pioneers and risk takers. For a young Black kid from Texas to see that and then later to be able to be in a room with that and get direct education and conversation…. It's an experience that not everybody gets to experience, and I'm grateful that I did, and hopefully we can do it again.

In 2022, you acted in Elvis. What are the biggest things you've learned from expanding into new creative areas?

I really have to give it up to a guy named Jeremy Grody…I went to his studio with these terrible demos that I had done on Pro Tools…and this guy helped save them and recreate them. I realized the importance of quality recordings. Jeremy Grody was my introduction to the game and really set me up to have the confidence to be able to step in rooms like that again.

I played some songs in the film, and I really understood how long a film day was. It takes all day long, a lot of takes, a lot of lights, a lot of big crews, big production.

I got to meet Lou Reed [while screening the film] at the San Sebastian Film Festival, and I was super nervous in interviews. I was giving away the whole movie. And Lou Reed said, "Just relax and have fun with all this s—." I really appreciated that.

Do you have a dream role?

I don't have a dream role, but I do know that if I was to get into acting, I’d really dive into it. I would want to do things that are challenging. I like taking risks. I want to push it to the limit. I would really like to understand what it's like to immerse yourself in the character and in the script and do it for real.

You're about to go out on tour. How will the show and production on this tour compare with the past ones?

We're building it currently, but I'm excited about what we got in store as far as the band goes. There are a few additions. I've got my sisters coming out with me. It's just going to be a big show.There's a new energy here, and I'm excited to share that with folks.

Photo: Alysse Gafkjen

interview

On New Album 'Speak To Me,' Julian Lage Blurs His Universe With Other Jazz Heavies

Julian Lage has released four winning albums on Blue Note Records, and he's still gaining momentum. His eclectic new album, 'Speak to Me,' reflects "different chapters in one story."

Can two different types of songs happen at once, and not clash, but complement each other?

On "Northern Shuffle" — the second track on his new album, Speak to Me — Julian Lage is trying to do just that.

Therein, his rhythm section of bassist Jorge Roeder and drummer Dave King mostly lay back — and Lage and saxophonist Levon Henry go to town.

"You have a shuffle feel, but then you have these somewhat irrational bursts of all the rubato things," guitarist and composer Lage tells GRAMMY.com from his home in New Jersey. "It's almost like a Paul Motian tune mixed in with a blues. That's a cool study of two different worlds somehow coming together."

These cross-currents make Speak to Me come alive. The six-time GRAMMY nominee's first three albums for Blue Note Records — 2021's Squint, 2022's View with a Room and 2023's The Layers — stuck with a narrower aesthetic, and winningly so.

"I actively tried to limit the scope of the last handful of records I've made so that it would be — let's say, electric guitar trio-dominant," Lage explains.

But on Speak to Me, which arrived March 1, Lage merges his universe with others' — that of innovative pianist Kris Davis, woodwind maestro Levon Henry and keyboard extraordinaire Patrick Warren. Plus, he doesn't solely pick electric or acoustic — like Neil Young, and other greats of both instruments, he splits the difference.

From opener "Hymnal" to closer "Nothing Happens Here," Davis, Henry and Warren flow along with Lage's working trio, where Roeder and King comprise the base of the triangle.

"It's just six people playing and listening and responding, and that's it. That's the record," Lage glows. "That was a beautiful thing about this particular group of people — that they were looking at it from an improvisational point of view, not a worker bee point of view."

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Last time I saw you play, you were accompanying Kris Davis at the Village Vanguard. Can you start by talking about your creative relationship with her?

I'm glad you were at that show. That turned out to be a nice record — Kris's band.

Kris and I met through our mutual friend, [writer, poet and record producer] David Breskin. This was years ago. She did a record [in 2016] called Duopoly. I hadn't played with Kris and didn't know Kris. I knew of her.

So, David said, "Kris is making this record." And he played a part in it. He said, "Let's just book the session. You come by and record a couple of duo songs and see how they go."

It really was an immediate connection. And it was just fun and beautiful. Those songs ended up on the record and then, every six months, eight months, we would find ourselves in a situation where we would play some duo shows.

And then, as she put together that week at the Vanguard, I was so honored to be invited to be in the band and then make that record. As we were getting Speak to Me together, and I was thinking of who to include, who to invite, it just seemed like this natural progression to ask Kris to come into the album and merge our worlds.

And I'm so glad she was a part of it. She's incredible.

Can you talk about how the rest of the Speak to Me contributors constellated?

Well, on the record, it's Dave King on drums and Jorge Roeder on bass, and Patrick Warren on keyboards, Levon Henry on woodwinds, and Kris on piano. Jorge and Dave comprise what has been my working trio for several years.

So, that's the center of the ensemble. And then Patrick and Levon and Kris — as Joe Henry would call it — create these weather systems that pass through the frame at any given moment.

It is important to me — to all of us — that they didn't feel like they're interlopers in the working trio. Because that's a danger you run into when you have a new ensemble mixing with a more established band.

And much to our delight, that's not at all what happened. Everyone created a space and held a space for it to become something unique in and of itself. Not a trio plus, but a genuine sextet or quintet at times. And it's all orchestration. What I like about it is it stems from improvisation, so no one has parts.

What was going on in your musical life that engendered this freewheeling spirit?

[Long pause, sigh] I don't know! [Chuckles]

I like writing songs a lot. And for a recording, in the past at least, I've written a lot more than we use. I have just a fascination with exhausting everything you can think of, and then I like that approach. And then once the cast is in place, editing out the pieces that don't feel like they celebrate the nature of those players. Really focusing on the pieces that endear themselves to this particular group.

And at the time, what I noticed was: a lot of the music I was writing was spiritual in nature, in the sense that a lot of them were refrains. They weren't rhythm changes; they weren't modern jazz tunes.

You hear that on something like "Nothing Happens Here," or "Hymnal," or "Speak To Me," or "South Mountain." A lot of these tunes could be played as rolling, rubato pieces; they could have a groove. They could be really any number of things.

So, an answer to your question: I think that what was going on for me at that time — evidently, just from what I hear on the record — is looking for music that has a certain amount of clarity and also a lot of space around it. That's the music that I needed to play, I needed to hear and be a part of just for my own sanity. I feel like I wrote the music to calm my own system down — or to nurture it, to maybe be more accurate.

And that type of writing lends itself well to freedom, and to everybody contributing whatever they contribute. Almost more in the spirit of Carla Bley or somebody, who writes these incredible pieces where the architecture is so fluorescent, but it's also invisible. Like you're left with just, What are the players contributing? So, I think this is healing music.

Can you think of any records in the overall jazz canon that acted as a prototype, or an archetype, for what you're doing on Speak to Me?

Let me frame it this way, perhaps: my true nature really is split between acoustic guitar and electric guitar. That's a simple divide.

And so, the main thing for me on this record was just not shutting out that other world. Not shutting out the acoustic in favor of the electric, and not shutting out the electric guitar for the acoustic, and the way the band responds around each instrument is so distinct.

So, you get a lot of mileage out of just shifting the guitar — because everyone's touch also shifts, and also their decisions shift. And instead of tenor saxophone with the electric guitar songs, there's clarinet with the acoustic.

As far as records in the jazz canon, the real prototype and archetype is the Duke Ellington Orchestra. Probably him the most, but also Count Basie — or any larger jazz ensemble where the whole point is that you can use variety and surprise to give a sense of innovation, but it's always held together by the songs.

In many respects, Speak to Me, as a record, is more aligned with an older era of jazz just by its variety — which isn't that varied, as things go. For me, it is. But if you listen to it enough, you realize, Oh, it is just one band. It's one statement. It's just different chapters in one story.

So, I would definitely look to Billy Strayhorn and Duke as huge influences for this album.

I love "Omission." It makes me feel like I'm riding through the Hollywood Hills listening to Blue or something. How did you dig into that aesthetic so believably?

I was trying to write a song for Charlie Watts, basically, is what was going through my head. And although I'm aware of Laurel Canyon and that sound, it wasn't…

Not that I'm saying you were actively trying to do that!

Oh, no, no, no, I took no [umbrage with that]. Even I hear it, and I'm like, Holy cow, that sounds like that, too!

But going into it, I was really mesmerized by Charlie — his beat on "Loving Cup." So, I was playing these different songs that fit to that beat. But frankly, because I had no desire to really reference something that overtly, I scratched the song from the record date.

We were in the studio for about two and a half days. On the first day, we did most of it. On the second day, we basically finished it. And then at some point, I talked to Joe and I just said, "I don't think this is good for the record, but I have this melody stuck in my head." And he said, "Well, just start playing it and we'll figure it out." So, then, he played it and everyone played a part, and that was it.

In a lot of ways, it's as much a surprise to me as anyone, how that presents. And it's funny, because I've since played that song live without an acoustic guitar in a jazz trio format as a completely different piece, and it's equally exciting to me. Because it's about the theme to me, more than the treatment.

But that record just so happened to capture that particular treatment, which is cool. I love that that happened, but it wasn't terribly deliberate, is all I can say.

Can you talk about tunes like "Northern Shuffle" and "76," where you get playful and dig into the blues in a subtly irreverent way? Blues is intrinsic to jazz, as we all know, but this is a different thing.

It is, really. It's part of the music. And also, those are shuffles. The shuffle feels are even more specific once you're in the world of jazz. And I love them, and Dave King plays shuffles better than anyone. They're just amazing.

I'd say "Northern Shuffle" is a cool example of really two songs happening at once. You have a shuffle feel, but then you have these somewhat irrational bursts of all the rubato things. It's almost like a Paul Motian tune mixed in with a blues. That's a cool study of two different worlds somehow coming together.

And I started as a blues guitar player, so pointedly that it feels only appropriate. "76" is similar. That's a little bit more straightforward in terms of the feel, but then you have Kris Davis playing on it in this way that brings in the world of avant-garde in a different way.

So, yeah, it's just a play of oppositional things in a way that to us as a band, aren't that dissimilar. The avant-garde, improvised music and blues is one thing. So those songs are about that.

But it's nice that they have a tinge of just a different aesthetic, a different growl. But because they're coming from the space of improvised music, they make sense with the other songs too.

The first time I interviewed you, it was around the time of Squint. You said something that stuck with me — that when you watch old videos of yourself, you almost feel like you were better then, because you weren't thinking about it as much. What's the state of your thinking on that?

Well, I appreciate that sentiment still. I think often as a younger player, it's easy to look to the future and go, Well, this isn't good, but down the road, I'll be good. It's baked into any practicing musician's mind.

But often, in my experience, when I look back at older stuff or I listen back, I can hear the person. Despite my insecurities or desires to get better, there was always somebody there, you know what I mean? There's someone there.

And maybe with some perspective and time, I can just appreciate that person and go, "Wow, way to go. Yeah, you didn't possess what you possess now, but who cares? You were doing that thing that you did at that time." So it's more just an appreciation for it than anything.

So, I do feel that when I hear things — absolutely.

We Pass The Ball To Other Ages: Inside Blue Note's Creative Resurgence In The 2020s

Photo: Elizabeth Leitzell

interview

Meet The First-Time Nominee: Lakecia Benjamin On 'Phoenix,' Dogged Persistence & Constant Evolution

"I decided the best thing I could do is to take my future into my own hands," says the ascendant alto saxophonist. Lakecia Benjamin shares her road to the 2024 GRAMMYs, where she's nominated for three golden gramophones for 'Phoenix.'

Lakecia Benjamin didn't call her last album Pursuance just because it's a Coltrane tune. Sure, that guest-stuffed 2020 album paid tribute to John and Alice — but also to Benjamin's indomitable doggedness.

And over Zoom — where she looks crisp and prosperous in futuristic, trapezoidal glasses and a chunky, ornate gold necklace — Benjamin's tenacity is palpable.

"You've got to just say, Until the day I die, I'm not going to stop," Benjamin declares to GRAMMY.com. "I only have one gig today. Okay, tomorrow I'll have two. The next day I'll have three, and I'm not going to leave. I'm not going to stop. Oh, I don't have a record deal. I'm not stopping."

So much could have tripped her up for good: The jam sessions she was laughed out of, with a dismissal to "Go learn changes." The epic cat-herding session for Pursuance, which could have fallen apart completely. The car accident she suffered in 2021, on the way home from a gig, which could have easily been fatal.

Benjamin just wanted 2023's Phoenix to be a worthy entry in her growing discography. The jazz saxophonist didn't have GRAMMY dreams; she didn't even presume it would be more successful than Pursuance.

Now, Phoenix is nominated for three golden gramophones at the 2024 GRAMMYs: Best Instrumental Album, Best Jazz Performance ("Basquiat") and Best Instrumental Composition ("Amerikkan Skin").

"I was just trying to tell my story about what happened to me, what's continuously happening to me," Benjamin says of Phoenix, which was produced by four-time GRAMMY-winning drummer and composer Terri Lyne Carrington. "Just trying to give people an idea of what it's like to be resilient, what it's like to not give up, what it's like to fight.

Read on for an interview with Benjamin about her journey to the GRAMMYs, and where she unpacks her personal dictum, which should apply to creatives the world over: "Keep going. Keep going. Keep going."

This interview has been edited for clarity.

What role have the GRAMMYs historically played in your life?

I remember being a little kid, watching the GRAMMYs and all. As a musician, at least in America, it's the highest award you can get.

It's something that you dream about. You dream about being nominated. You dream about walking on that stage. You dream about being in that audience, seeing your other peers and superstars performing. I personally dreamed about the red carpet.

Are there past jazz nominees that you found super inspiring?

All of them, really. Chick Corea, Christian McBride, Ron Carter, Terri Lyne, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter. There are just so many.

I first interviewed you for JazzTimes about your album-length tribute to John and Alice Coltrane, Pursuance. What was the underlying theme of Phoenix?

Just the idea that things are possible. You don't have to get things done in a certain timeline, in a certain frame. You just have to keep going, with a lot of determination. That was my goal.

I did not think that the reception would have been bigger than Pursuance. There's no way I saw that coming. It's been a really wild rollercoaster year, for sure.

Working with Terri Lyne Carrington was a huge step. It seems like you were swinging for something bigger. What was that thing?

She was actually the catalyst for the whole thing. I picked her before I even had the music — everything — because I wanted someone that could get the best out of me. Someone who's going to tell me the truth, tell me when it's not good enough, tell me what's not possible.

I felt that the guests that I have picked in mind — and they had already agreed to the project — were in her sphere of people that she's worked with. I felt she could understand my dedication in this project to highlight women musicians, and to highlight [how] women musicians have had to climb the ladder, and sometimes they fall back down and climb back up again.

I felt that her story is a true testament of that. I just felt she embodied where I am right now, and what I'm trying to do.

Terri Lyne commands such a musical universe. You could have made Phoenix with so many different configurations and ensembles. What made these particular folks perfect to tell your story?

The fact that [pianist] Patrice Rushen started as a jazz musician, moved into the pop world, super megastar, back into the jazz world, back into the trenches, still teaching and still educating.

Angela Davis — a huge iconic figure — had her own adversities. They all represent in their own stories the idea of persevering, the idea to keep going, but also doing that while operating at an extremely high level.

As a musician myself, there's always self-doubt about the past. I wish I did this when I was younger, I wish I made this choice, I wish I pushed harder, blah, blah. But it took until my thirties to realize that I have all this life to live. I don't have to cram everything into the now and beat myself up. It seems like you had a similar moment of self-realization.

I guess I still have those struggles as well too. I think we all do, but I think you start to realize you're alive right now.

You can't control what you did 10 years ago. You can't control what you did five years ago. You can only control what's happening right now, and you could sit around and sit in that regret and doubt, and that becomes your story. Or, you could choose to get up and decide, I'm going to make a new reality for myself. I'm going to brand myself, and I'm going to try to accomplish the things that I'm dreaming about.

Why dream about, If I had known this 10 years ago, I would've did this? But it's right now, you know it. You can go ahead forward and try to get there. You don't have to listen to other people's limitations, the part of their life and their reality. But it's not a part of yours.

We're all on Jazz Instagram. We see everyone competing over gigs and vibing each other out. It seems like you're trying to get out of that rat race and be like Terri Lyne, where it's a whole life — a continuum.

That's what I started thinking. Even as a bandleader, everyone's in this pool, crabs in a barrel trying to drag each other down, waiting for a call, waiting to say, "I have more gigs," waiting to say, "I have more GRAMMYs," and I decided the best thing I could do is to take my future into my own hands.

If I become a bandleader, if I'm making the calls, I'm the one doing this. I have a little bit more control, and then I can choose to say, You know what? I'm going to try to live out my dreams, and if it doesn't work out for me, I can die knowing I gave it my all. I did everything I can to get the things I want in life.

And to me, that's enough — if I know that I've tried the very best I can to do something.

What helped you get out of that tunnel-vision mindset?

I wouldn't say I'm all the way out of it, because those thoughts creep in; you're programmed this way. But I do think you have to just say, There's no other road I can take. I'm going straight. I'm not going through the sewer. If there's a roadblock, I'm not going to the left. I'm going straight down this road.

When I did Pursuance [I thought], You know what? I got all 45 of these cats up in here. I did it myself, on my dime, on my time, the way I wanted to do it.

After that, there's immense pressure. What's going to happen with Phoenix? Is it going to be good enough? Is it going to be this? And to know I was able to tell my own story. I was able to get these guests the same way, figure it out, get this music together and get it together, lets me know that I may be crawling to get there, but I'm getting there.

I'm moving forward, and I'm doing it in a way that I'm getting better as an artist. I'm not just getting more, I guess, accolades and noteworthy my actual talent is because I'm choosing to put the music first.

Here's a spicy question. How have people treated you differently now that you're a first-time GRAMMY nominee?

It's only happened recently, but it is drastically changing. I will say that. There are some people that this whole year, the last two years, it started to seriously change. There are people that went from thinking, I'm just an ambitious girl out there, "Good luck. She's trying her best," to taking me a little bit more seriously when I have these [nominations]; they're not dreams anymore. They're like, "She's making things happen."

Where are you at in your development as a saxophonist? What's the status of you and the horn?

I've got a long way to go, but you spend three years playing Coltrane, you'll definitely expedite the process of: at each gig I'm forced to be at a certain level, minimum.

I think I'm making some progress — and we'll have to battle that out with Terri Lyne, but I think I'm getting better, and that's the most important thing. I wish I could expedite that a little faster, but these albums are just pictures of where I am at the time.

John and Alice were such outstanding models for how to live a creative life.

It's inspiring. I tell you that. For everyone out there that is wondering how to keep pushing forward, how not to give up, every time you get a minor victory, that's another example of going the right way.

My first two albums were projects that were more, let's say, ear friendly. You would think people would gravitate to that more because they understand that music is more contemporary, and they [performed] decently.

But then I come out with this Coltrane project and it does exponentially better, and that's being true to myself, then I do another project that's even deeper into the pool of what it's supposed to be, and then has even more success.

I just think that we got to spend less time trying to find these gimmicks, and people really respond when something is authentic, when it's a live show and they see you pouring your soul out there authentically, that's what gravitates them — not trying to find a way to get over on them.

"Get over on them." What do you mean by that?

I feel like that's what a gimmick is. If I say, I'm going to hold this note for 10 minutes because the audience will really love it. I'm trying to find a way to convince them that this is good, this is cool.

I'm like, Let me dress up in this outfit, because this'll convince them. Rather than just coming out and just being like, This is who I am. This is what it is. And putting it all on the stage, and then they can see authentically, This is who I'm voting for.

Do you see a lot of charlatans out there in the jazz scene, just trying to dazzle with cheap tricks?

I will say that I pray for humanity to be more authentic.